“Blessed in the sight of heaven is the place called Conewago…”

Pope St John XXIII

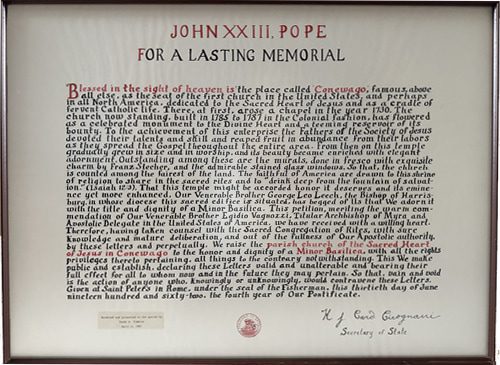

Pope St John XXIII decreed the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Hanover, PA a minor basilica in 1962, formally acknowledging the historic, artistic, and pastoral renown of Conewago. Since the early 19th century, however, a series of artists, under the patronage of the resident Superiors and Provincials of the Society of Jesus, were already declaring the glory of Sacred Heart on its walls and ceilings. An ever-expanding decorative program, including key commissions in 1844 and 1850, culminated in 1887 under the unifying vision of the artist Lorenzo C. Scattaglia (1846-1931). Drawing on the style and architectural organization of the great Baroque churches of Rome, most notably the Jesuit Church of the Gesù, Scattaglia visually harmonized the works of his artistic predecessors at Sacred Heart into a scheme that proclaims the triumph of the Church and, by association, the triumph of the Jesuits in the Conewago valley.

The Jesuit impulse to glorify the Church and her doctrines in art and architecture arose in the age of the Counter Reformation, a period of heightening fervor among the Catholic laity. Earlier in the century, the Church’s initial response to the Protestant Reformation was marked by austerity and a retreat from the type of grand artistic commissions that marked the decades leading up to 1517. In the years following the close of the Council of Trent in 1563, however, the renewed vigor in the faith, in part inspired by new religious orders such as the Jesuits, demanded a reimagining of the image of the Church, an image that projected power and might even in the face of those who dared to attack Her. The times called for an architecture of awe-inspiring grandeur and a pictorial aesthetic of dramatic persuasion that could arouse devotion.

The mother church of the Jesuits, the Chiesa del Santissimo Nome di Gesù, known simply as the Gesù, in Rome, is a model of this new impulse. [See the second in our series on the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for a thorough description of the interior decoration of the Gesù.] Consecrated in 1584 and decorated at the end of the 17th century, the whole church interior, in both its architectural aesthetic and in its pictorial content, is a celebration of the triumph of the Catholic Church. The use of classical architectural elements on a massive scale as well as the application of precious materials – colored marbles, inlaid stone, and gilding – proclaim splendor and magnificence throughout the building. Meanwhile, the fresco of the Triumph of the Name of Jesus (1672-83) by Giovanni Battista Gaulli seemingly bursts through the nave vault with breathtaking illusionism. The image of the IHS – the monogram of Jesus Christ and emblem of the Society of Jesus – hovers in the blinding golden-white light of the heavens as figures spill across the architectural frames and the ceiling coffers. The scene appears to reach down physically to the worshiper below while simultaneously drawing him up spiritually into the glory pictured above. The triumph of the Church becomes an almost tangible reality at the Gesù.

At the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Hanover, PA, as at the Gesù in Rome, the church interior is a complete celebration of the Church and Her teachings. [See the first in our series on the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for a thorough description of the decorative program restored by Canning Liturgical Arts in 2023.] Scattaglia’s extensive use of tromp l’oeil creates the illusion of grand Baroque architectural ornament, monumental in scale and seemingly embellished by precious materials. The colossal pilasters of the nave, the massive ceiling panels, and the plaster cornice frieze running the perimeter of the church interior provide a triumphal scaffolding for the pictorial decoration. The theme of the triumph of the Church is then conveyed in the content of the three main decorative components of the church: the Assumption of Mary (1844) by Gebhart of Philadelphia in the nave ceiling; the cycle of the Wonders of Divine Love (1850) by Franz Stecher in the ceiling vaults of the transept and crossing; and Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament (1850) by Stecher in the semi-dome of the apse. The Assumption grants a glimpse of the glory of heaven in the golden light that surrounds Mary as she rises. As she looks upward into that light and opens her arms, ready to embrace her Son once again, the scene anticipates her Coronation as Queen of Heaven. Similarly, Stecher’s three ceiling paintings of the Wonders of Divine Love illustrate the movement of the Trinity from glory to greater glory: from the north transept vault in which Christ is shown removing his crown and preparing to empty himself to take the form of a servant (Philippians 2:7); to the south transept in which Christ returns to the right hand of the Father, the crown and the cross now both synonymous with His triumph over death; to the culminating scene at the crossing, itself crowned in a frame of gilded plaster, in which Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are superimposed with tiara, scepter, and Sacred Heart ablaze on the chest of Christ, signs of the consummate triumph of Divine Love. Finally, in the apse, it is the Sacrament itself that is crowned in the glory of the golden rays of heaven. The monstrance in the shape of the Sacred Heart soars above the sanctuary, framed by Scattaglia’s classically-derived triumphal arch crowned with the monogram “IHS,” seal of the Society of Jesus. Just as the image of the IHS monogram in glory at the Gesù conveys powerfully both the triumph of the name of Jesus and the triumph of the Society of Jesus within the Church, so too the image of the Sacred Heart rising in glory in the apse at Hanover expresses both the triumph of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ and the triumph of the Jesuits in Conewago.

In his 1962 decree declaring Sacred Heart a minor basilica, Pope St John XXIII remarked that Conewago was “famous, above all else, as the seat of the first church in the United States, and perhaps in all North America, dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.” Devotion to the Sacred Heart has a history dating back to the early church, but since the 17th century it has been linked particularly with the Jesuits. In a series of visions in the years 1673-75, Jesus appeared to St Margaret Mary Alacoque, a Visitation sister, and revealed his wish to be honored with the image of His heart. St. Claude de la Colombière, SJ, rector of the Jesuit community at Paray-le-Monial and spiritual director of the Visitation sisters, supported St Margaret Mary’s claims and promoted the devotion to the Sacred Heart. In 1856 Pope Pius IX established the Feast of the Sacred Heart for the universal Church, and in 1883, at the 23rd General Congregation of the Society of Jesus, it was decreed that “the Society of Jesus accepts and receives with a spirit overflowing with joy and gratitude, the gentle burden that our Lord Jesus Christ has entrusted to it, to practice, promote, and propagate, devotion to His most divine Heart.” The monumental oil on canvas, the Vision of the Sacred Heart to St Margaret Mary (1887) by Filippo Costaggini, celebrates that special Jesuit “burden.” Located in the Sacred Heart apse behind the altar and below Stecher’s Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, the painting illustrates the moment that Christ reveals his Sacred Heart to St Margaret Mary. The bust of Colombière piously watches over the mystical scene, his presence an indication of the role he and the Society of Jesus will play in spreading this devotion. Installed to replace a mural of the Last Supper (1850) by Stecher which had been irretrievably damaged by water, Costaggini’s painting makes for an earthly complement to the beatific vision in Stecher’s Adoration above: the apse ceiling is a vision of the triumph of the Blessed Sacrament and, simultaneously, the Sacred Heart while the canvas below brings glory to the devotion of the Sacred Heart and the Jesuits who promoted it.

The Jesuits at Conewago had particular reason to feel triumphal in their efforts to persuade, teach, and inspire devotion. John T. Reily in his Conewego: A Collection of Catholic Local History (1885) frames the history of Catholic Conewago in terms of the “heroic virtue” of the early Jesuit missionaries who, through their “labors, sufferings, and deaths are as inspiring as the Lives of the Saints or the Trials of the Early Martyrs.” (Conewago, 7-8) Indeed, the Jesuits were the earliest Catholic evangelizers to the English colonies, a presence in this part of the New World from 1634. Their impact was profound both in preaching and converting the Indigenous people and in cultivating a fervent Catholic faith and culture from Maryland and Virginia, and from Philadelphia to the frontiers of Pennsylvania. Standing on a hill overlooking that vast agricultural country, Sacred Heart was, of course, the heart of those missions. And like the Gesù in Rome that stands as a symbol of the victory of the Church over Protestantism, Sacred Heart proclaims its own triumph as heroic evangelizer and “redeemer” of this new land. (Conewago, 9)

The dedication of Sacred Heart as a minor basilica in 1962 was a recognition that the church exists not just as a place of worship but as a locus of identity. When the interior decorative program reached its zenith in 1887 under Scattaglia’s unifying artistic vision, Sacred Heart fully expressed the triumphal self-conception of the resident Jesuits: they were the great celebrants of the doctrines of the Church; they were the passionate propagators of the Sacred Heart devotion; and they were the heroic evangelizers of the New World. All of this, of course, was in service to the greater glory to God. Long after the Jesuits left Sacred Heart in 1901, the essence of this identity remained with the diocesan priests and the people of Conewago. In his 1962 decree Pope St John XXIII declared Sacred Heart “a cradle of fervent Catholic life…counted among the fairest in the land.” In 2023 Canning Liturgical Arts restored the interior decoration of Sacred Heart to its 1887 artistic heights, allowing the Basilica to stand in triumph once again in the heart of rural Pennsylvania, truly to be counted among the fairest in the land.

Written By Amy Marie Zucca, Ph.D.

Amy Zucca is the resident art historian for John Canning & Co. and Canning Liturgical Arts. With a doctorate in art history and a specialization in the Italian Renaissance, Amy brings historic insight to our projects, new art commissions and design work for the company. If you have a painting you’d like to have evaluated for its historic significance or are interested in commissioning artwork for your sacred space, please contact Amy directly at amy@johncanningco.com.