Giacomo della Porta, emblem of the Society of Jesus above the central portal, 1575, Church of the Gesù, Rome (detail of façade).

“The early Catholics, scattered within the bounds of the outlying missions, once looked to Conewago for all the spiritual aid they ever received.” John T. Reily

From at least 1637, when the first English missionaries tended to the earliest settlers, Catholic Conewago was formed and cultivated by the Society of Jesus, commonly known as the Jesuits. High on a hill in Hanover, in the heart of Pennsylvania’s agricultural country, these missionaries constructed the first little log “Conewago Chapel,” the spiritual NorthStar that John T. Reily describes in Conewago: A Collection of Catholic Local History (1885). Under continued Jesuit administration, a stone structure was built in 1787 and then enlarged in 1850-51. Then over the course of three key commissions in 1844, 1850, and 1887, prompted by the energy and enthusiasm of the Superiors and Provincials of the Society of Jesus, the interior of the Church – now Basilica – of the Sacred Heart of Jesus was organized visually and theologically into a grand, unified decorative program. [See the first in our series on the Basilica of the Sacred Heart for a thorough description of the decorative program restored by Canning Liturgical Arts in 2023.] By the end of the nineteenth century, Jesuit leadership had brought Sacred Heart to the height of its artistic expression.

Peter Paul Rubens, St. Ignatius of Loyola, c. 1620-22, oil on canvas, Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena

The inspiration for this ambitious program in rural Hanover is rooted in the history of the Society of Jesus, especially in their church building and decorative projects of 17th-century Rome. Founded in 1534 by St. Ignatius Loyola, the Jesuits is an order of religious men, professing vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, especially obedience to the pope in matters of their missions and service in the world. Fired up by a missionary spirit and a fervor for the Faith, the Jesuits along with other new orders – the Theatines founded by St. Cajetan of Thiene in 1524, the Capuchins founded by Matteo da Bascio in 1525, and the Oratorians founded by St. Philip Neri in 1575 – spurred on the age of the Counter Reformation. These new orders not only defended the Faith but emboldened the common people to aspire to an active and dynamic Christian life. In the years after the close of the Council of Trent in 1563, the Jesuits were preaching to huge congregations, and the demand for church buildings that could both accommodate those crowds in structure as well as arouse the spirits of the faithful through decorative programming became increasingly urgent.

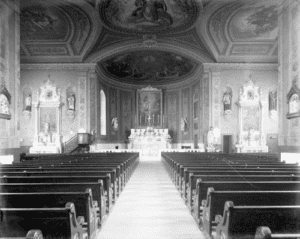

Left: View of nave looking toward sanctuary, Church of the Gesù, Rome. Right: View of nave looking toward sanctuary c. 1900, Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hanover, PA.

The mother church of the Jesuits, the Chiesa del Santissimo Nome di Gesù, known simply as the Gesù, in Rome, became not only the model for Jesuit churches but was famously credited by the great architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83) as having “perhaps exerted a wider influence than any other church of the last four hundred years.” (Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture, Penguin, 1957, p. 232) Designed by the architect Giacomo da Vignola (1507-1573) in 1568 and consecrated in 1584, the Gesù introduced the church ground plan favored through the Baroque period of the 17th century: a wide, longitudinal nave, uninterrupted by aisles or columns, with short transepts, and a dome over the crossing. Pairs of colossal, two-story pilasters frame the side chapel entrances on either side of the nave and are crowned with richly carved Corinthian capitals. These support a massive, molded cornice that runs the entire perimeter of the church interior and provides a baseline for the vast barrel vault above the nave. Embellished throughout with inlaid stone, polychrome marble, and gilding, the effect of the great space and the splendor of the architecture is powerful. As an English traveler of 1620 described the Gesù: “…wherein is insertd all possible inventions, to catch mens affections, and to ravish their understanding…” (qtd. in Francis Haskell, Patrons and Painters: Art and Society in Baroque Italy, Yale, 1980, p. 63).

Left: Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Triumph of the Name of Jesus, 1672-83, fresco and stucco, Gesù, Rome (detail). Right: Gebhart of Philadelphia, Assumption of Mary, 1844, Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hanover, PA.

It would be nearly 100 years after the construction of the church, though, before the Gesù reached its decorative heights with the fresco of the nave vault. The Triumph of the Name of Jesus (1672-83), painted by Giovanni Battista Gaulli (1639-1709) from Genoa, is a showcase of the Baroque: extreme in size, astonishing in its illusionism, and breathtaking in the drama of its composition. IHS – the monogram of Jesus Christ and the emblem of the Society of Jesus – bursts through the blue sky in a blinding golden halo of light, framed by an airy mass of tumbling cherubs. Crowds of twisting and turning saints portrayed in thrilling foreshortening, float on clouds gathered on the edges of the divine light. Meanwhile, gathered in the darkness below the clouds are the damned, a writhing horde of tortured bodies. Figures, both saints and sinners, spill across the architectural frames and ceiling coffers, the limits of the painted and the spectator’s realities disregarded in a feat of optical illusionism. Stucco figures, designed by Gaulli and executed by Antonio Raggi (1624-86), perch on the nave cornice and appear to respond to the action in the vault. The merging and mingling of the arts – of architecture, painting, and sculpture – create a total work of art, a Gesamtkunstwerk, a symphony of a visual experience that strives to proclaim the Jesuit motto: Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam, to the greater glory of God.

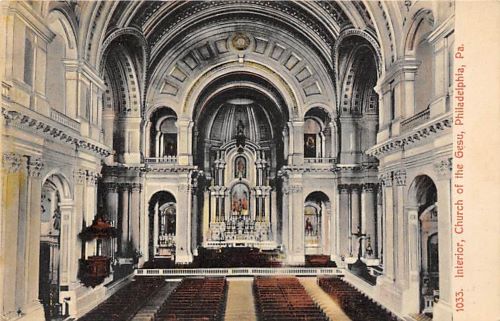

View of nave looking toward sanctuary, Church of the Gesù, Philadelphia, PA (c. 1905)

It is this aspiration, to glorify God through the art and architecture of liturgical space, that is the legacy of the Jesuits and their mother church, the Gesù. In the United States, this was manifested in places such as the Church of the Gesù, Philadelphia, built 1879-1888 (closed 1993) with decoration inspired by Rome and the Church of St. Ignatius, New York, built 1895-1898, which, although more classically Renaissance in design, nevertheless captures the grandeur of the 17th century in its luxurious mixing of materials, such as inlaid stone and polychrome marbles. However, the first American heir to the Baroque ambitions of Rome is, of course, Sacred Heart in Hanover, PA.

Like the Gesù, Sacred Heart was made for a popular audience to inspire awe and surprise. Indeed, the luxurious Baroque-revival interior hidden behind the restrained Federalist exterior is delightfully unexpected. As in Rome, the ground plan is longitudinal with a broad nave and a painted dome-like (circular cupped) space above the crossing. The colossal, two-story pilasters with tromp l’oeil faux marble finishes and the cornice frieze, flowing around the entire perimeter of the church interior, allude to the lavish architectural ornamentation of the Gesù. Although the materials are more modest at Sacred Heart, achieving the visual effect of something more grand and costly via masterly illusionistic painting is itself a characteristic Baroque device, again intended to surprise and delight. And while the centerpiece of the nave ceiling of Sacred Heart does not exhibit the dramatic rupturing of the painted space beyond the boundaries of the frame as in the Triumph of the Name of Jesus, the ceiling is nevertheless a completely ornamented surface in the Baroque tradition. Adorned with monumental tromp l’oeil coffers, intricately woven floral decorations, gilded frames, and a great window to the heavenward Assumption of Mary, it is the first expression of a Jesuit aesthetic on American soil.

Restoration of the cornice frieze and molding, Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hanover, PA (2023)

A final question arises, though: how did this vision for a unified Baroque-revival decorative program come to rural Hanover? As described by Reily in his history of Catholic Conewago, the driving motivators to build, enlarge, and decorate Sacred Heart were the Jesuit Superiors and Provincials, most notably Fr. Joseph Enders, S.J. (1806-1884), Superior at Conewago in 1847-1862 and 1871-1884. However, there is little evidence to demonstrate that these religious men, although enthusiastic fundraisers, had any part to play in devising the decorative programs or in making stylistic choices. In fact, Reily notes that when the German-born artist Francis Stecher was employed 1850-51 to decorate the recently enlarged portion of the church, that “to [Stecher’s] skill and taste Conewago is indebted for the beautiful adornment of its walls.” (Reily p. 73) Note that it is the “skill and taste” of the artist that is responsible for the decoration; no credit is given to the patron. Historically, this was true of the Jesuits as well. The building of the Gesù in Rome was accomplished through the patronage of the powerful Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (cardinal 1534, d. 1589) while the later decoration of the side chapels was dependent on the financial contributions of wealthy secular patrons. Each decorative plan, then, was guided by the money and the independent taste of an individual or family. (Haskell p. 67) There was no true or consistent “Jesuit style” in 17th century Rome any more than there was in 19th century Conewago.

Left: View of nave looking toward sanctuary, Church of the Gesù, Rome.Right: View of nave wall looking toward choir loft, Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hanover, PA.

However, a general Jesuit aesthetic originated at the Gesù, which brought together architectural design and ornamentation with painting and sculpture in an overall effort to glorify God, would likely have been introduced to Sacred Heart through the artist Lorenzo C. Scattaglia (1846-1931). Born in Italy and emigrating to the United States in 1874, Scattaglia kept a studio in Philadelphia and worked as a decorative artist for many Catholic churches in the area, including St. Joseph Church, Hanover (razed 1963); St. Peter’s Cathedral, Scranton; St. John the Evangelist, Pittston; and St. Joseph, Baltimore. Scattaglia’s Stations of the Cross (1877-80) made for St. Joseph Church, Hanover, (now in the collection of the State Museum of Pennsylvania) demonstrate that his figurative painting style was more in the controlled, classical tradition of Raphael rather than the excited, theatrical approach of Gaulli. However, as a student of the High Renaissance, he likely spent time studying and working in Rome, and would most certainly have visited and been familiar with the great Baroque churches, including the Gesù. When he was hired in 1887 by the resident Jesuits to create a new unifying decorative scheme for Sacred Heart, a scheme that included much of the tromp l’oeil architectural ornamentation restored today, he must have been working under the inspiration of the famous Mother Church in Rome.

Scattaglia’s work brought to culmination more than a century of Jesuit architectural and artistic ambition in Conewago. Then, less than fifteen years later, in 1901 administration of Sacred Heart transferred from the Jesuits to the Diocese of Harrisburg, and in the decades to follow much of the interior decorative program was lost. Water and other surface damage as well as changes in artistic taste and fashion prompted interventions and overpainting that largely disrupted or effectively concealed the nineteenth-century painted scheme.

In 2023, though, Canning Liturgical Arts revealed and restored all that the Jesuit missionary priests sought to raise on that rural hill in Hanover: a Mother Church in her own right. The “Mother Church to the Pennsylvania missions.” The “Mother Church of the Diocese of Harrisburg.” The “Mother Church of Pennsylvania west of the Susquehanna.” In 2023 Catholics can look to Conewago again.

Written By Amy Marie Zucca, Ph.D.

Amy Zucca is the resident art historian for John Canning & Co. and Canning Liturgical Arts. With a doctorate in art history and a specialization in the Italian Renaissance, Amy brings historic insight to our projects, new art commissions and design work for the company. If you have a painting you’d like to have evaluated for its historic significance or are interested in commissioning artwork for your sacred space, please contact Amy directly at amy@johncanningco.com.