The question of whether beauty is objective or subjective remains a contentious and deeply personal debate. The words truth and goodness are often paraded along with beauty to affirm its place among the objective. While the subjective approach finds public life, experience, and taste are far too diverse to settle on a single “correct” version of beauty and therefore, surely its definition belongs to the eye of the beholder. In the world of art and architecture, the controversy relating to this question rests not only in the argument itself, but even more sensitively on the very definition of art. What makes something art? Can anything be art?

The ancient Greeks understood beauty as a kind of spiritual entity that indicated a higher order. According to Plato, beauty played an active role in the development of the human spirit and in making an ideal real. He writes in the Symposium, “Beholding beauty with the eye of the mind, he will be enabled to bring forth, not images of beauty, but realities, and bringing forth and nourishing true virtue to become the friend of God and be immortal, if mortal man may.” Beauty retained a spiritual approach from the birth of philosophy in ancient Greece until the age of the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment.

Aphrodite Head, 3rd Century The Birth of Venus, Botticelli, 1485-86 Venus and Cupid, The Honey Thief, Picasso, 1960

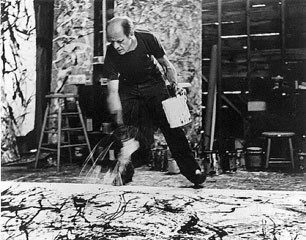

Between a scientific rationalization of the natural world and the elevation of human emotion during the Romantic Period, a manifestation of Enlightenment ideology, art began to shift from aesthetic beauty to the purity of individual expression and emotion. This change reversed the relationship between art and beauty. Art, once a skill in service to beauty utilized to unlock the transcending graces of a higher realm, became a thing unto itself, unbeholden to beauty. Today even skill is unnecessary to the creation of art, only expression is required. This approach to art focuses on the randomness of life. It insults human ability and creativity by requiring none. It abandons the human soul and imagination in preferring ugliness and monotony to the sacred existence of beauty. Art of this kind is only diverse in so far as it refuses to give merit to its creation.

Franz West Exhibition, 2019, Tate Modern, London

The Romantic Movement reduced the concept of art to expression and the modernists collectively distilled it into anything and nothing at all. This approach has deliberately attempted to do away with the ancient understanding of art, the way many have done with religion, as explained by Marcel Duchamp in a 1968 BBC interview. The champions of modernism may believe this approach has conquered beauty, but it is exactly there where the answer to the folly may be found. These artistic movements of the late millennium have only been successful in redefining the meaning of art by deterring creativity.

The Visionary Ecstasy of Death, Bernini, 1674 Fountain, Marcel Duchamp, 1917

Perhaps as a result of our highly scientific culture, all things have come to demand a kind of material means of measurement. Unlike the cultures of the past, the wondrous and indescribable, previously attributed to the divine, are now inferior to that which may be proven in a laboratory or by a research panel. So, when a thing cannot be measured scientifically or reproduced by a formula, it is found to be subjective. It is impossible to prove or determine the limitations of beauty by a standard of measurement. As a result, beauty has been deposed by the sterility of technicalities and reclassified into oblivion by relativism.

But maybe the whole argument of whether beauty is either objective or subjective is wrong altogether. It would seem that beauty is neither free from the opinions and feelings of humanity nor wholly dependent upon them. Truely beauty cannot be contained, formulated, or defined. So the real question is, does it exist? Is it even real? I dare say it does and I believe most all would agree, for all have encountered beauty in one way or another. The vastness of the experience of beauty ranges from a summer storm and the spires of a cathedral, to the touch of a baby’s hand and the sorrow of a funeral march. It captures the heart and mind in perfect contentment. Beauty is to be found in hope and love, pain and loss. Experiences of beauty are extremely varied and diverse, but consistent in the majesty, wonder, and peace blessed upon the individual. In beauty there is confirmation in sorrow and affirmation in joy. These encounters with beauty make individual experience relatable to others and life itself, worthwhile. Perhaps most importantly, when something is beautiful it elevates human existence to a higher good.

Perfect beauty is unwanting; requiring neither addition nor subtraction to improve. And though there is no formula for the creation of the beautiful, those things designed with fitness, proportion, and harmony result in a state of repose (Owen Jones, Grammar of Ornament, Proposition 3). An impressive guide to architecture and decoration was written by 18th century architect and designer, Owen Jones. His book, The Grammar of Ornament, contains 37 propositions for the construction of architecture and ornament as well as various styles of decoration. The origin of these proportions is found in the natural world and historically, the building materials were also familiar to the region. In this way, construction and artistic expression are manifestations of observations made in the natural world, glorified by human creativity, and designed to inspire.

Created things must be proportional to that which they represent, therefore a church, destined from conception as a sacred monument, must be a material expression of the beauty it aims to impart in the teachings of tradition and faith. For this reason, beautiful and cool are not interchangeable since cool is lacking in the sacred mystery bound up in the beautiful. “Hence beauty consists in due proportion; for the senses delight in things duly proportioned, as in what is after their own kind—because even sense is a sort of reason, just as is every cognitive faculty. Now since knowledge is by assimilation, and similarity relates to form, beauty properly belongs to the nature of a formal cause.” (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I, Q. 5, Art. 4)

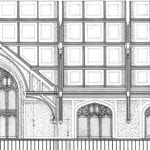

St. Francis de Sales, North Shores, MI, Marcel Breuer, 1950 St. Mary Church, Boston, MA, Patrick Keely, 1882

As an example, the two churches featured here depict interiors with high ceilings, relatively simple color palette, and a feeling of magnitude. There are many differences but perhaps the most overwhelming is the direction of the energy in the architecture and decoration. The attenuating forms at St. Mary Church draw the eye upward in comparison to the downward direction in the design of St. Francis de Sales. The heavy manner and ordinary material of the modern church offer little redemption for the soul of humanity. While St. Mary takes the ordinary, wood, plaster, stone and glass, and transforms them into something extraordinary. The warmth of the carved wood, the soft light of the palette, and the stories illustrated in the windows, not only satisfy curious eyes but also creates a place in the world that both literally and figuratively represents a higher good. St. Mary’s appeals to the intellect, the heart, and curiosity subsequently providing the human being with a sense of belonging.

No quantifiable proof of beauty is required to know that it exists everywhere: in everyday life, the faces of those we love, in awe of great art, even in tears. Humanity yearns for the extraordinary and finds peace in wonder. Beauty makes us come alive, it dignifies humanity beyond the physicality of nature and gives purpose to life through inspiration and redemption. In this way, beauty is transcendent, as if emitting golden rays of warm sunlight from moments, objects, persons, and beliefs. It is therefore impossible to avoid the spiritual existence of beauty, as described by the ancients, since it is evident yet intangible.