A History of Notre Dame de Paris: Resilience, Restoration & Renewal

“…the façade of Notre Dame, as we see it to-day, when we stand lost in pious admiration of the mighty and awe-inspiring Cathedral, which, according to the chroniclers, strikes the beholder with terror - quæ mole sua terrorem incutit spectantibus.”

-Victor Hugo, Hunchback of Notre Dame

The expression “standing the test of time” takes on a new meaning when looking through the many pages in the history of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. The structure has graced the Parisian skyline for hundreds of years but not always in the same form. The church took roughly 100 years to complete, mastering the art of Gothic Cathedral design. The magnificent and impossible nature of Gothic cathedrals inspire terror and awe. The towers that reach for the heavens becoming thinner and even more decorative as the spires touch the sky were by design intended to represent the prayers of the faithful soaring into the heavens. From the underlying design to the simplest decoration, everything in Gothic design serves to worship the Glory of God.

Gothic architecture flourished for a brief moment, especially in France. The rise of the Renaissance brought new styles and ideals leading to the destruction of many Gothic buildings in Paris but Notre Dame and other church buildings remained untouched by the new mode. It was during the Renaissance that Gothic architecture received its name. The return to Classicism regarded Gothic architecture as a departure from true Christian principles of belief and design. The term Gothic was coined as a derogatory term derived from Goths, a people who contributed to bringing the Western Roman Empire to its knees. This classification put Gothic architecture in the context of savages and questioned whether beauty could develop from such an uncivilized people.

WITHSTANDING THE TEST OF TIME

The French Revolution

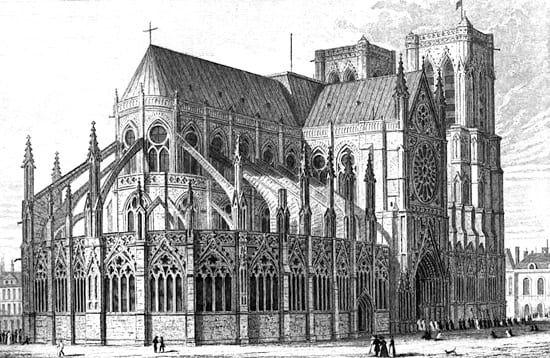

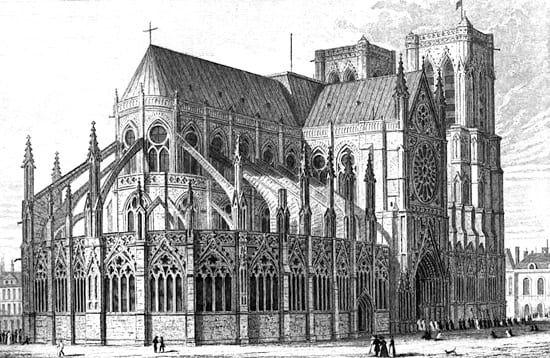

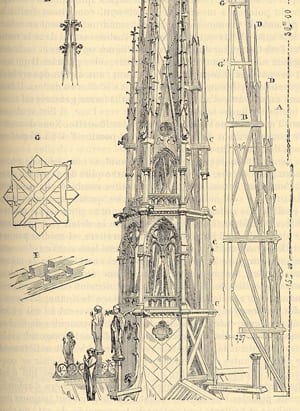

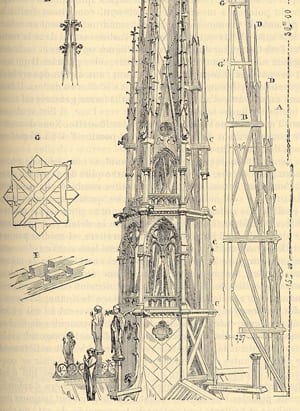

The French Revolution ravaged the church, striped her of precious artwork, statues and melted down bells for military purposes. The revolutionaries decapitated the French nobility as well as statues that represented the Kingdom of France and the Catholic Church. Law, order, and faith were butchered. The country turned to philosophy and reason to guide their new establishment but philosophy without truth leads to violent ends justified by unbounded reason. The revolution inspired men to become their own gods and buildings of faith become the victims of ideologies. It was during the revolution that the iconic spire, la fleche, weakened in the wind and lead to its removal from the roof. The drawing above is a study by Augustus Pugin, depicting the church prior to restoration and without the iconic spire. The church was repurposed as a storeroom for the war and later as a temple to reason. Violated and neglected, Notre Dame suffered during the Revolution but defied the time and lived to see another era.

Victor Hugo’s Influence

In Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre-Dame, he described Notre Dame Cathedral as a once inspiring and majestic structure left to the forces of neglect. Two whole chapters of the novel outline the history of the Cathedral and its current state. Hugo forced Parisians to look beyond their noses and up at this incredible church once again. He inspired France to restore Notre Dame in all her glory and reminded the people not only of the building’s physical value and beauty but of the value the church had in all of their hearts. War left the Cathedral in a state of disrepair, and today a fire is to blame. Both tragedies inspired France to rebuild and restore the precious heart of Paris.A New Paris: Rebuilding of the City Under Napoléon III

During the rebuilding of Paris commissioned by Napoléon III, the city was remodeled to adapt to the modern time. The revolution left the city weak, pillaged and behind compared to the likes of London, New York and Berlin. Baron Haussmann, Prefect of the Seine under the Emperor, lead these extensive renovations redesigning Paris to bring air and light into the city. Notre Dame was restored by Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, who notably replaced the spire atop the Cathedral among many other restorations. The square in front and the gardens surrounding Notre Dame were designed during this period, allowing due admiration of the church from many perspectives and preventing the church from being swallowed by new buildings in the city.

Portrait of Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc by Nadar

The Restoration of Notre Dame Cathedral

Viollet-le-Duc emphasized the importance of historical and archival research in order to capture the original intent of each piece contributing to the Cathedral. He analyzed every alteration, renovation, and injury. In a letter during the years of research spent on Notre Dame, Viollet-le-Duc cautioned:In such a project one cannot operate with too much prudence and discretion. To state it plainly, a restoration can be more disastrous for a monument than the ravages of centuries and popular upheavals, for time and revolutions destroy but do not add anything. To the contrary, a restoration can, by adding new forms, obliterate a host of vestiges, the peculiarity, singularity, and antiquity of which add interest (Viollet-le-Duc, The Architectural Theory of Viollet-le-Duc: Readings and Commentaries).

Study of the Notre Dame spire, la flèche, 1859.

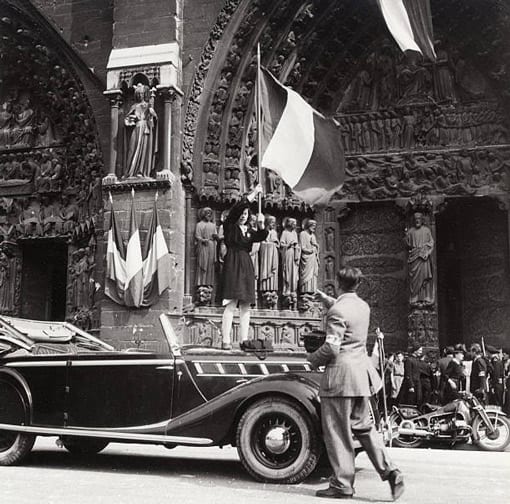

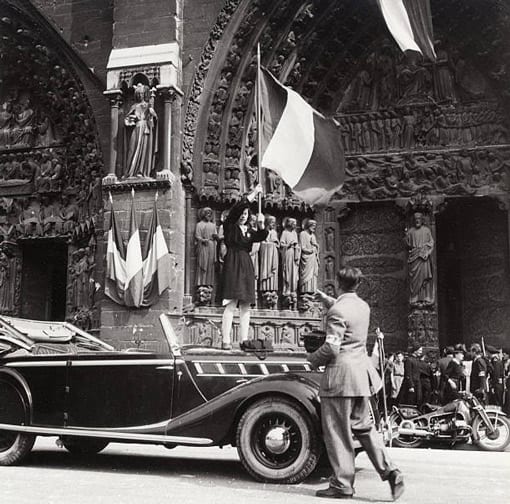

World Wars

Two world wars came and left France leaving a wake of death and destruction. In the First World War, the Germans came within 20 miles of Notre Dame de Paris. During both wars, the Cathedral risked bombings and the cruel effects of military conflict. Nazi terror generated a new kind of beast, a new war of ideologies. Churches and buildings designed to inspire, faced intentional demolition to prove philosophical points. General Dietrich von Choltitz, Nazi governor in Paris during the war, proved an unexpected hero to the city’s architectural history. Despite his reputation for following command orders blindly, in response to Hitler’s plans to destroy historic buildings in Paris he replied, "I cannot implement this insane order" (Randall Hansen, Disobeying Hitler: German Resistance in the Last Year of WWII). Perhaps Choltitz is to thank for the preservation of Notre Dame during the Second World War.APRIL 15, 2019, 18:50

On Monday, April 15, the world watched in disbelief as Notre Dame Cathedral burned in a hellfire that lasted hours into the night. This fire may be one of the greatest tragedies in the history of art and architecture. This miserable event brought immeasurable sorrow. The fire sent Our Lady’s Arrow soaring into the heart of Paris as the delicate spire collapsed in the flames. How quickly 800 hundred years of Catholic tradition, beauty, art and architecture were snuffed out before our eyes. Often tragedy amplifies what is truly important, as Notre Dame has brought the world together to mourn this loss of history and beauty. The fire has reminded the world the importance of beauty and that buildings like Notre Dame cannot be taken for granted. While the flames leapt from the Île de la Cité, hearts poured out in song, eyes in tears, and donations flooded the Cathedral to see the beloved Notre Dame resurrected from the ashes.

As we take solace in the idea that Notre Dame de Paris was once rebuilt and make efforts that she will once again rise to in all her former architectural glory, let us not forget the ringing words of Viollet-le-duc regarding the fundamental purpose for renovation and renewal. Though not Catholic, he considered the “restoration of a building whose usefulness is still as real, as indisputable today as on the day of completion; of a church, in short, erected by a religion whose immutability is one of its fundamental tenets” (Viollet-le-Duc, The Architectural Theory of Viollet-le-Duc: Readings and Commentaries). Notre Dame should not and will not become an architectural graveyard for the beliefs for she was designed are as relevant today as in 1163. The bravery of the firefighters, the rescue of the relics and precious artwork, the voices of song and tears of sorrow from all corners of the earth are testament to the love for Notre Dame that surpasses physical affection and touches on spiritual devotion.